Dear Readers,

Wishing you a happy and hopeful New Year. As 2026 begins, it offers not just fresh starts but sharper clarity, an opportunity to rethink the systems we depend on in a climate that is no longer predictable. Climate Threads is our effort to demystify climate science, connect it to real-world impacts on people, society, and the economy, and explore practical, positive ways to navigate climate risk in our everyday lives.

The Economy Meets the Weather

At 6:15 a.m., the operations head of a mid-sized logistics company in western India opens his dashboard expecting a routine day. Overnight dispatches are queued, delivery timelines are tight, and penalties for delays are non-negotiable. Within the first thirty minutes, the plan begins to unravel.

A stretch of the national highway connecting an industrial cluster to the port has been shut down. Intense overnight rainfall has flooded low-lying sections of the road, not enough to make headlines, but enough to halt heavy vehicles. Trucks are rerouted through longer state highways. Fuel consumption rises. Delivery windows shrink. Drivers edge closer to legal working-hour limits.

By noon, the cost becomes visible. Two export consignments miss the port cut-off. Demurrage charges begin to accumulate. A client flags a contract violation. What was meant to be a routine logistics day now carries a measurable financial loss: lost time, higher operating costs, and reputational damage.

No disaster has been declared. No emergency sirens sound. Yet the balance sheet has already taken a hit.

This kind of disruption increasingly reflects a new operating reality rather than an exception.

Critical Infrastructure: The Backbone at Risk

For most businesses, climate change does not arrive as a headline about global warming. It arrives as a system failure.

These moments feel sudden, even accidental. But they are not random. They are signals of critical infrastructure under stress, the invisible backbone through which climate risk is translated into economic loss.

An assessment published as part of the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes this explicit: climate impacts are increasingly mediated through infrastructure systems, rather than occurring only as direct physical damage to assets. Businesses do not experience climate change as degrees celsius or millimetres of rainfall; they experience it as power outages, transport delays, water shortages, communication failures, and operational shutdowns.

From climate signals to business disruption

Climate science tells us what is changing: hotter days, heavier rainfall bursts, stronger cyclones, rising seas. Businesses feel how those changes matter through infrastructure.

This transmission mechanism is critical. A World Bank assessment on disaster economics notes that infrastructure failure accounts for a substantial share of indirect economic losses from climate extremes, often exceeding the value of direct physical damage to assets. In other words, what hurts balance sheets most is not always what is destroyed, but what stops working. This is why infrastructure sits at the centre of climate risk for India’s economy.

Critical infrastructure refers to physical and digital systems essential for economic activity, public safety, and everyday operations. Their failure does not affect one firm alone; it cascades across sectors and regions.

A recent peer-reviewed study published in Public Library of Science (PLOS) Climate shows that India’s climate has already shifted beyond historical baselines, with rapid warming, increasing monsoon variability, and intensifying compound extremes. Researchers found that average temperatures across India have risen by nearly 0.9 °C over the last decade, contributing to more frequent and severe heatwaves and erratic rainfall patterns, while the Arabian Sea has warmed rapidly, boosting the intensity of pre-monsoon cyclones and coastal storm surge risks. These changing hazard patterns are already making legacy design assumptions increasingly unreliable for infrastructure that was built on historical climate norms.

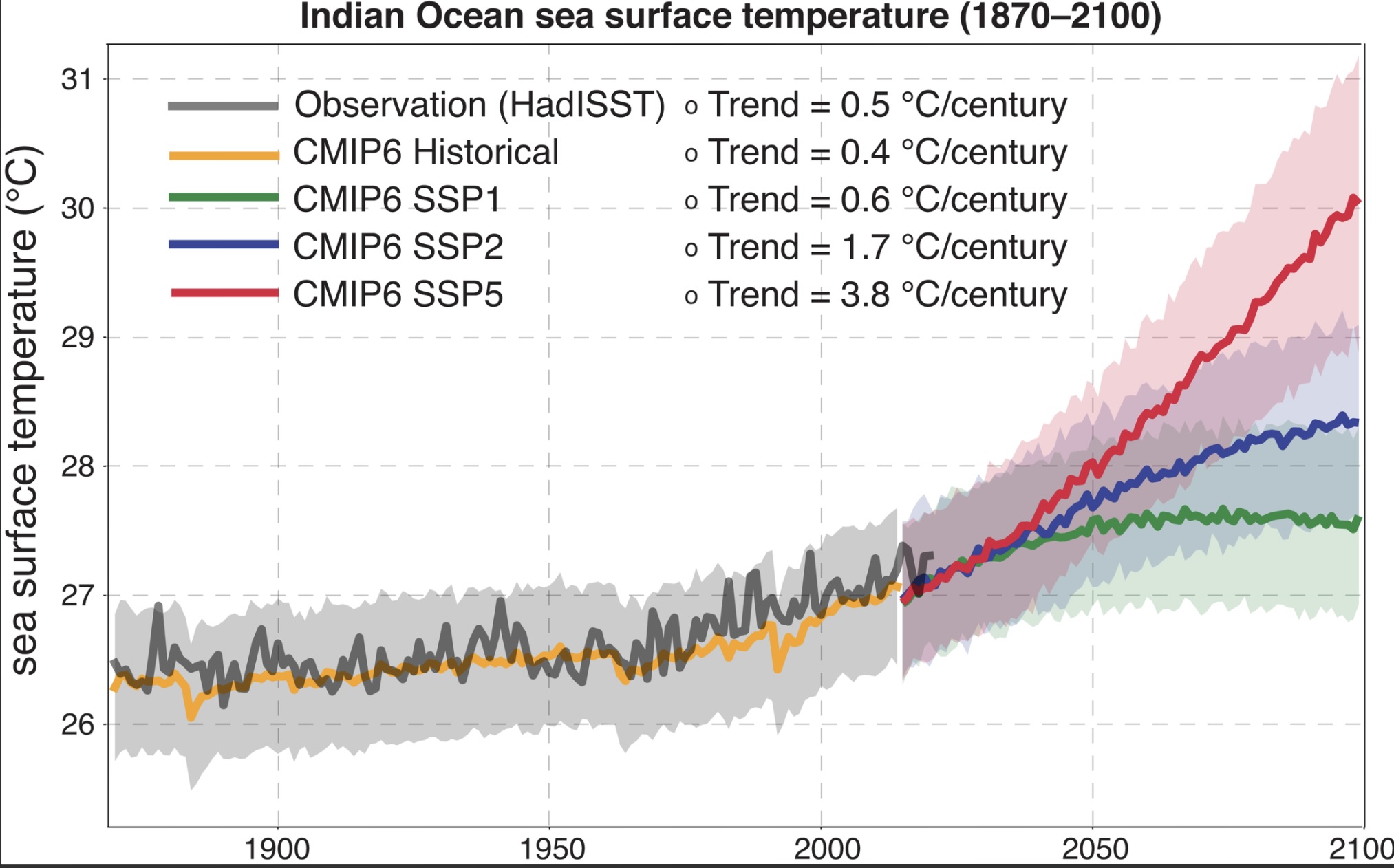

Figure 1 – Warming of the tropical Indian Ocean under different emissions pathways

Figure 1. Taken from the same peer-reviewed assessment on observed and projected climate change in India, the figure illustrates how warming in the tropical Indian Ocean has already departed from historical variability and is projected to accelerate further under continued global warming. Observations show a clear long-term rise in sea surface temperatures since the late nineteenth century, closely matched by CMIP6 climate model simulations. Looking ahead, the divergence between emissions pathways becomes stark: under a low-emissions scenario (SSP1-2.6), warming stabilises by mid-century, while under intermediate (SSP2-4.5) and high-emissions (SSP5-8.5) pathways, ocean temperatures continue to rise sharply through 2100. The assessment shows that this warming is neither uniform nor benign, higher sea surface temperatures intensify atmospheric moisture, fuel stronger cyclones, raise coastal heat stress, and amplify extreme rainfall, with cascading implications for infrastructure and businesses concentrated along India’s coastline and monsoon-dependent regions.

Why do infrastructure hotspots matter: $2.4 Trillion at stake by 2050

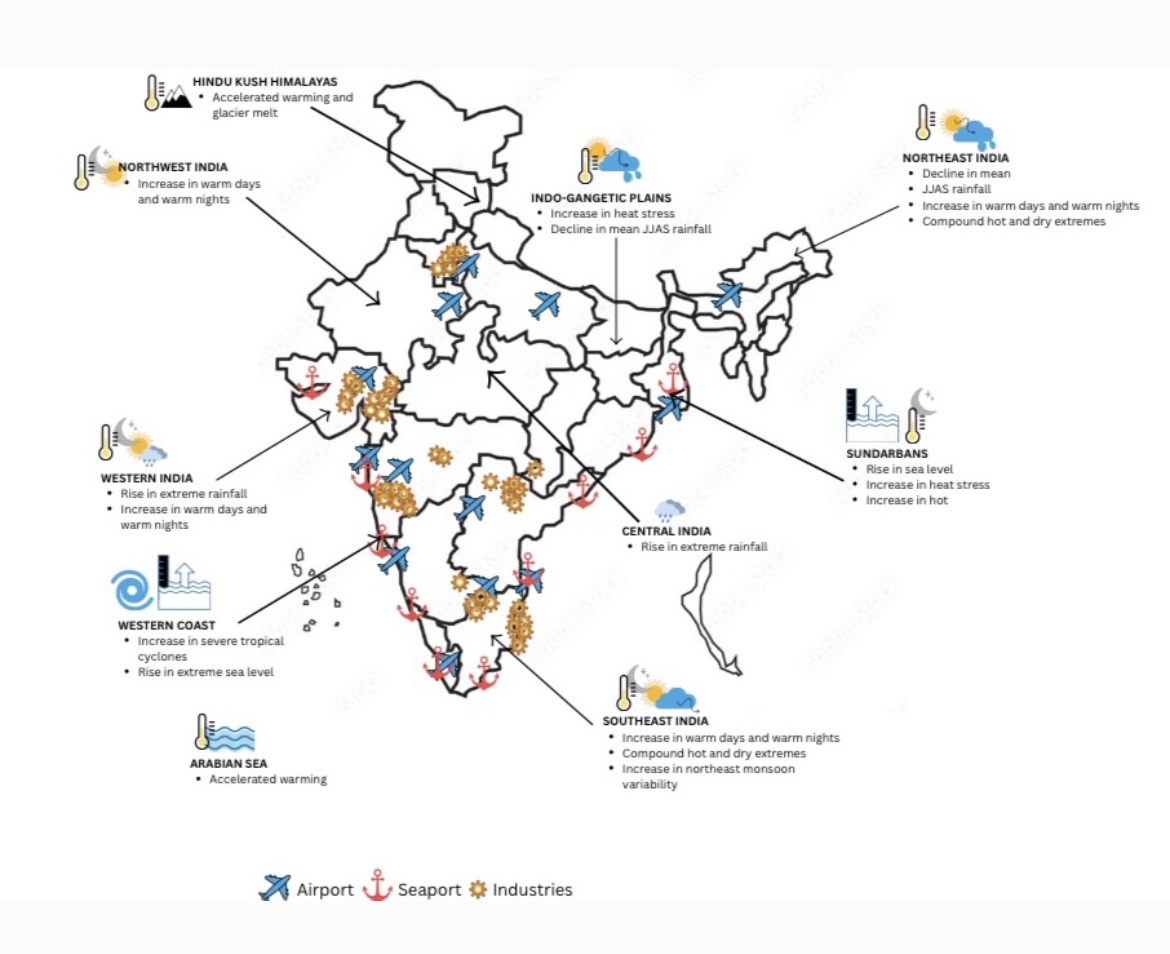

The hotspot visual (Figure 2) maps airports, seaports, and industrial assets against future climate hazards projected under continued warming across India. It draws on the same analysis, which combines long-term observations with CMIP6 climate model projections to assess how climate risks evolve as temperatures rise through mid-century. The paper identifies spatially differentiated climate hotspots by linking regional warming trends to changes in hazard behaviour, showing where extreme heat intensifies, short-duration rainfall events become more severe, cyclones strengthen in a warming Arabian Sea, and sea-level rise amplifies coastal flood risk. Rather than reflecting historical exposure alone, the analysis explicitly connects these hazards to warming-driven increases in their frequency, intensity, and compounding nature, providing a forward-looking view of where infrastructure stress is most likely to concentrate. The visual highlights three overlapping dimensions of risk:

- Type of asset: the category of infrastructure exposed, such as airports, ports, and industrial regions

- Degree of exposure: how intense and frequent hazards are becoming

- Type of hazard: heat stress, rainfall anomalies, flooding, cyclones, or sea-level rise

Figure 2 – India’s economic backbone in climate hazard hotspots

When these layers overlap, risk becomes systemic rather than local.

Climate hazards are not only increasing in frequency and intensity, they are already translating into large economic losses for India’s infrastructure. As per a report jointly published by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), in India alone, transport assets worth an estimated $400 billion are exposed to climate hazards such as floods and cyclones, with knock-on effects that ripple through manufacturing, agriculture, and services if supply chains are interrupted.

When hazard patterns change, the implications for infrastructure are not abstract; they are regional, cumulative, and deeply economic. Consider India’s western coastline, historically less exposed to frequent severe cyclones than the east. Ports, airports, industrial corridors, and urban centres along this coast were therefore designed for lower storm intensity and limited storm surge. Today, warming in the Arabian Sea is altering that risk profile. Stronger cyclones are now intersecting with sea-level rise, extreme rainfall, rising heat stress, and an increase in warm nights, creating compound hazards in one of India’s most economically active regions. For infrastructure clustered along the coast, this means more frequent operational shutdowns, damage to high-value assets, and repeated business interruption rather than one-off losses. The consequences extend beyond physical damage: disrupted trade flows, stranded capital investment, lost jobs, and heightened risks to lives and livelihoods in dense urban and industrial zones. When ports, airports, power systems, and transport links are exposed to multiple, overlapping hazards, recovery slows and losses compound, turning regional climate stress into systemic economic risk.

For example, a recent World Bank assessment finds that Indian cities will need more than $2.4 trillion by 2050 to build resilient infrastructure capable of withstanding heatwaves, floods, and sea-level related stressors as urban populations grow. Urban flooding already costs an estimated $4 billion annually in economic losses, a figure projected to rise to $30 billion by 2070 without adaptive investment.

Changing Hazard Patterns & their Impact on Critical Infrastructure

Table 1

Across sectors, India’s critical infrastructure was built for a climate defined by historical averages; predictable heat, moderate rainfall, and infrequent extremes. That baseline is now shifting. Power systems, transport networks, ports, water infrastructure, and urban clusters are increasingly exposed to climate stresses that exceed their original design assumptions, turning routine operations into sources of repeated disruption.

In the power sector, infrastructure designed for short summer heat peaks is now facing prolonged heatwaves. India’s peak power demand crossed 240 GW in recent summers, with record-breaking loads during heatwaves. High ambient temperatures reduce transformer efficiency while simultaneously increasing cooling demand, a compounding risk.

Transport systems reveal how small physical stresses create outsized economic effects. Roads and highways, designed for moderate rainfall and gradual drainage, are increasingly disrupted by short-duration, high-intensity rainfall that overwhelms drainage systems. The PLOS Climate assessment referenced earlier shows an analysis using long-term India Meteorological Department rainfall data that shows extreme rainfall events have increased sharply even in regions where total rainfall has declined.

Ports and airports, as high-value economic nodes, face concentrated climate exposure. Many west-coast ports were built for historical cyclone patterns and lower storm-surge levels. The assessment documented warming trends in the Arabian Sea that support stronger cyclones.

Water and wastewater systems are under dual stress. Longer dry spells reduce water availability for industry, while intense rainfall overwhelms drainage and sewage infrastructure. As this study also highlights this dual stress: declining moderate rainfall days reduce groundwater recharge, while extreme events increase flood risk.

The risks extend into telecom and data infrastructure, which depend on stable power, cooling, and physical access. Heatwaves raise cooling loads in data centres, while floods disrupt access and power supply. When digital systems fail, disruptions ripple across sectors simultaneously.

Finally, urban housing and industrial clusters amplify vulnerability through density. Built for speed and cost rather than resilience, many urban systems lack adequate heat mitigation and drainage capacity. Urban heat islands intensify temperature extremes, while flooding disrupts labour availability and slows recovery, particularly in informal economic settings.

Together, these stresses show how climate change increasingly affects the economy not through dramatic destruction, but through repeated system strain. Infrastructure failure has become the primary channel through which climate risk reaches balance sheets.

From Risk to Readiness: Building our Readiness for a Changing Climate

Climate risk becomes a balance-sheet issue when critical infrastructure fails. The real danger lies where climate stress overlaps with economic concentration, areas where disruptions repeat and losses compound. Climate change does not need to destroy assets; it only needs to push systems beyond their design limits. What is required is not alarm, but adjustment. By making infrastructure risk visible, through exposure mapping, supply-chain stress-testing, and resilience planning, businesses can shift from reacting to disruption to anticipating it. In today’s climate reality, resilience is not caution; it is a competitive advantage.

In the next section, we shift from diagnosis to response, focusing on resilience and adaptation, how organisations can translate these insights into practical, scalable actions.

And the good news is that every step taken toward preparedness today is a step toward stronger, more confident operations tomorrow.